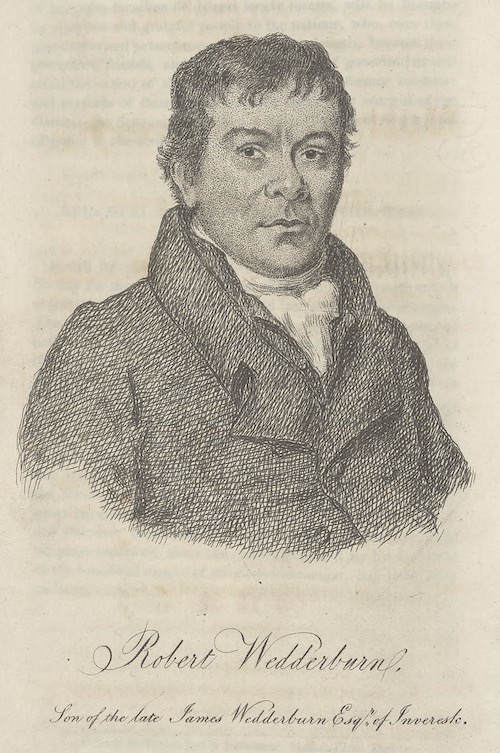

Image of Robert Wedderburn

Title Page

Dedicated to W. WILBERFORCE, M.P.

THE

Horrors of Slavery;

exemplified in

The Life and History

OF THE

Rev. ROBERT WEDDERBURN, V.D.M.

(Late a Prisoner in His Majesty’s Gaol at Dorchester, for Conscience-Sake,)

Son of the late JAMES WEDDERBURN, Esq. of Inveresk, Slave-Dealer,

by one of his Slaves in the Island of Jamaica:

IN WHICH IS INCLUDED

The Correspondence of the Rev. ROBERT WEDDERBURN

and his Brother, A. COLVILLE, Esq. alias WEDDERBURN,

of 35, Leadenhall Street.

With Remarks on, and Illustrations of the Treatment of the Blacks

AND

A VIEW OF THEIR DEGRADED STATE,

AND THE

DISGUSTING LICENTIOUSNESS OF THE PLANTERS.

LONDON:

PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY R. WEDDERBURN,

23, RUSSELL COURT, DRURY LANE;

And Sold by R. Carlile, 84, Fleet Street; and T. Davison, Duke Street,

West Smithfield.

1824

Letter to William Wilberforce

To

WILLIAM WILBERFORCE, Esq. M.P.

Respected Sir,

An oppressed, insulted, and degraded African—to whom but you can I dedicate the following pages, illustrative of the treatment of my poor countrymen? Your name stands high in the list of glorious benefactors of the human race; and the slaves of the earth look upon you as a tower of strength in their behalf. When in prison, for conscience-sake, at Dorchester, you visited me, and you gave me—your advice, for which I am still your debtor, and likewise for the two books beautifully bound in calf, from which have since derived much ghostly consolation. Receive, Sir, my thanks for what you have done; and if, from the following pages, you should be induced to form any motion in parliament, I am ready to prove their contents before the bar of that most Honourable House.

I remain, Sir

Your most obedient, and

most devoted Servant,

ROBERT WEDDERBURN

23 Russel Court,

Drury Lane.

The Life of Robert Wedderburn

LIFE

OF THE

Rev. ROBERT WEDDERBURN.

The events of my life have been few and uninteresting. To my unfortunate origin I must attribute all my miseries and misfortunes. I am now upwards of sixty years of age, and therefore I cannot long expect to be numbered amongst the living. But, before I pass from this vale of tears, I deem it an act of justice to myself, to my children, and to the memory of my mother, to say what I am, and who were the authors of my existence; and to shew the world, that not to my own misconduct is to be attributed my misfortunes, but to the inhumanity of a MAN, whom I am compelled to call by the name of FATHER. I am the offspring of a slave, it is true; but I am a man of free thought and opinion; and though I was immured for two years in his Majesty’s gaol at Dorchester, for daring to express my sentiments as a free man, I am still the same in mind as I was before, and imprisonment has but confirmed me that I was right. They who know me, will confirm this statement.

To begin then with the beginning—I was born in the island of Jamaica, about the year 1762, on the estate of a Lady Douglas, a distant relation of the Duke of Queensbury. My mother was a woman of colour, by name ROSANNA, and at the time of my birth a slave to the above Lady Douglas. My father’s name was James Wedderburn,, Esq. of Inveresk, in Scotland, an extensive proprietor of estates in Jamaica, which are now in the possession of a younger brother of mine, A. Colville, Esq. of No. 35, Leadenhall Street.

I must explain at the outset of this history—what will appear unnatural to some—the reason of my abhorrence and indignation at the conduct of my father. From him I have received no benefit in the world. By him my mother was made the object of his brutal lust, then insulted, abused, and abandoned; and, within a few weeks from the present time, a younger and more fortunate brother of mine, the aforesaid A. Colville, Esq. has had the insolence to revile her memory in the most abusive language, and to stigmatize her for that which was owing to the deep and dark iniquity of my father. Can I contain myself at this? or, have I not the feeling’s of human nature within my breast? Oppression I can bear with patience, because it has always been my lot; but when to this is added insult and reproach from the authors of my miseries I am forced to take up arms in my own defence, and to abide the issues of the conflict.

My father’s name, as I said before was James Wedderburn, of Inveresk, in Scotland near Musselborough, where, if my information is correct, the Wedderburn family have been seated for a long time. My grandfather was a staunch Jacobite, and exerted himself strenuously in the cause of the Pretender in the the rebellion of the year 1745. For his aiding to restore the exiled family to the throne of England, he was tried, condemned, and executed. He was hung by the neck till he he was dead; his head was then cut off, and his body was divided into four quarters. When I first came to England, in the year 1779, I remember seeing the remains of a rebel’s skull which had been affixed over Temple Bar; but I never yet could fully ascertain whether it was my dear grandfather’s skull or not. Perhaps my dear brother, A. Colville, can lend me some assistance in this affair. For this act of high treason, our family estates were confiscated to the King, and my dear father found himself destitute in the world, or with no resource but his own industry. He adopted the medical profession; and in Jamaica he was Doctor and Man-Midwife, and turned an honest penny by drugging and physicing the poor blacks, where those that were cured, he had the credit for, and for those he killed, the fault was laid to their own obstinacy. In the course of time, by dint of booing and booing, my father was restored to his father’s property, and he became the proprietor of one of the most extensive sugar estates in Jamaica. While my dear and honoured father was poor, he was chaste as any Scotchman, whose poverty made him virtuous; but the moment he became rich, he gave loose to his carnal appetites, and indulged himself without moderation, but as parsimonious as ever. My father’s mental powers were none of the brightest, which may account for his libidinous excess. It is a common practice, as has been stated by Mr. Wilberforce in parliament, for the planters to have lewd intercourse with their female slaves; and so inhuman are are many of these said planters, that many well-authenticated instances are known, of their selling their slaves while pregnant, and making that a pretence to enhance their value. A father selling his offspring is no disgrace there. A planter letting out his prettiest female slaves for purposes of lust, is by no means uncommon. My father ranged through the whole of his household for his own lewd purposes; for they being his personal property, cost nothing extra; and if any one proved with child—why, it was an acquisition which might one day fetch something in the market, like a horse or pig in Smithfield. In short, amongst his own slaves my father was a perfect parish bull; and his pleasure was the greater, because he at the same time increased his profits.

I now come to speak of the infamous manner with which James Wedderburn, Esq. of Inveresk, and father to A. Colvile, Esq No. 35, Leadenhall Street, entrapped my poor mother in his power. My mother was a lady’s maid, and had received an education which perfectly qualified her to conduct a household in the most agreeable manner. She Was the property of Lady Douglas whom I have before mentioned; and, prior to the time she met my father, was chaste and virtuous. After my father had got his estate, he did not renounce the pestle and mortar, but, in the capacity of Doctor, he visited Lady Douglas. He there met my mother for the first time, and was determined to have possession of her. His character was known; and therefore he was obliged to go covertly and falsely to work. In Jamaica, slaves that are esteemed by their owners have generally the power of refusal, whether they will be sold to a particular planter, or not; and my father was aware, that if he offered to purchase her he would meet with a refusal. But his brutal lust was not to be stopped by trifles; my father’s conscience would stretch to any extent; and he was a firm believer in the doctrine of “grace abounding to the chief of sinners.” For this purpose, he employed a fellow of the name of Cruikshank, a brother doctor and Scotchman, to strike a bargain with Lady Douglas for my mother; and this scoundrel of a Scotchman bought my mother for the use of my father, in the name of another planter, a most respectable and highly esteemed man. I have often heard my mother express her indignation at this base and treacherous conduct of my father—a treachery the more base, as it was so calm and premeditated. Let my brother Colville deny this if he can; let him bring me into court, and I will prove what I here advance. To this present hour, while think of the treatment of my mother, my blood boils in my veins; and, had I not some connections for which I was bound to live, I should long ago have taken ample revenge of my father. But it is as well as it is; and I will not leave the world without some testimony to the injustice and inhumanity of my father.

From the time my mother became the property of my father, she assumed the direction and management of his house; for which no woman was better qualified. But her station there was very disgusting. My father’s house was full of female slaves, all objects of his lusts; amongst whom he strutted like Solomon in his grand seraglio, or like a bantam cock upon his own dunghill. My good father’s slaves did increase and multiply, like Jacob’s kine; and he cultivated those talents well which God had granted so amply. My poor mother, from being the housekeeper, was the object of their envy, which was increased by her superiority of her education over the common herd of female slaves. While in this situation, she bore my father two children, one of whom, my brother James, a millwright, I believe is now living in Jamaica upon the estate. Soon after this my father introduced a new concubine into his seraglio, one Esther Trotter, a free tawny, whom he placed over my mother, and to whom he gave the direction of his affairs. My brother Colville asserts, that my mother was of a violent and: rebellious temper. I will leave the reader now to judge for himself, whether she had not some reason for her conduct. Hath not a slave feelings? If you starve them, will they not die? If you wrong them, will they not revenge? Insulted on one hand, and degraded on the other, was it likely that my poor mother could practise the Christian virtue of humility, when her Christian master provoked her to wrath? She shortly afterwards became again pregnant; and I have not the least doubt but that from her rebellious and violent temper during that period, that I have the same disposition—the same desire to see justice overtake take the oppressors of my countrymen—and the same determination to lose no stone unturned, to accomplish so desirable an object. My mother’s state was so unpleasant, that my father at last consented to sell her back to Lady Douglas; but not till the animosity in my father’s house had grown to such an extent, that my uncle Sir John Wedderburn, my father’s elder brother had given my mother an asylum in his house, against the brutal treatment of my father. At the time of sale, my mother was five months gone in pregnancy; and one of the stipulations of the bargain was, that the child which she then bore should be free from the moment of its birth. I was that child. When about four months old, the ill-treatment my mother had experienced had such an effect upon her, that I was obliged to be weaned, to save her life. Lady Douglas, at my admission into the Christian church, stood my godmother, and, as long as she lived, never deserted me. She died when I was about four years old.

From my mother I was delivered over to the care of my grandmother, who lived at Kingston, and who earned her livelihood by retailing all sorts of goods, hard or soft, smuggled or not, for the merchants of Kingston. My grandmother was the property of one Joseph Payne, at the east end of Kingston; and her place was to sell his property—cheese, checks, chintz, milk, gingerbread, &c; in doing which, she trafficked on her own account with the goods of other merchants, having an agency of half-a-crown in the pound allowed her for her trouble. No woman was perhaps better known in Kingston than my grandmother, by the name of “Talkee Amy,” signifying a chattering old woman. Though a slave, such was the confidence the merchants of Kingston had in her honesty, that she could be trusted to any amount; in fact, she was the regular agent for selling smuggled goods.

I never saw my dear father but once in the island of Jamaica, when I went with my grandmother to know if he meant to do any thing for me, his son. Giving her some abusive language, my grandmother called him a mean Scotch rascal, thus to desert his own flesh and blood; and declared, that as she had kept me hitherto, so she would yet, without his paltry assistance. This was the parental treatment I experienced from a Scotch West-India planter and slave-dealer.

When I was about eleven years of age, my poor old grandmother was flogged for a witch by her master, the occasion of which I must relate in this place. Joseph Payne, her master, was an old and avaricious merchant, who was concerned in the smuggling trade. He had a vessel manned by his own slaves, and commanded by a Welchman of the name of Lloyd, which had made several profitable voyages to Honduras for mahogany, which was brought to Jamaica, and from thence forwarded to England. The old miser had some notion, that Lloyd cheated him in the adventure, and therefore resolved to go himself as a check upon him. Through what means I know not, but most likely from information given by Lloyd out of revenge and jealousy, the Spaniards surprised and captured the vessel; and poor old Payne, at seventy years of age, was condemned to carry stones at Fort Homea, in the Bav of Honduras, for a year and a day; and his vessel and his slaves were confiscated to the Spaniards. On his way home he died, and was tossed overboard to make food for fishes. His nephew succeeded to his property; and a malicious woman-slave, to curry favour with him, persuaded him, that the ill-success of old Payne’s adventures was owing to my grandmother’s having bewitched the vessel. The old miser had liberated five of his slaves before he set out on his unlucky expedition; and my grandmother’s new master being a believer in the doctrine of Witchcraft, conceived that my grandmother had bewitched the vessel, out of revenge for her not being liberated also. To punish her, therefore, he tied up the poor old woman of seventy years, and flogged her to that degree, that she would have died, but for the interference of a neighbour. Now what aggravated the affair was, that my grandmother had brought up this young villain from eight years of age, and, till now, he had treated her as a mother, But my grandmother had full satisfaction soon afterwards. The words of blessed Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ were fulfilled in this instance: “Do good to them that despitefully use you, and in so doing you shall heap coals of fire upon their heads.” This woman had an only child, which died soon after this affair took place (plainly a judgment of God); and the mother was forced to come and beg pardon of my grandmother for the injury she had done her, and solicit my grandmother to assist her in the burial of her child. My grandmother replied, “I can forgive you, but I can never forget the flogging;” and the good old woman instantly set about assisting her in her child’s funeral, it being as great an object to have a decent burial with the blacks in Jamaica, as with the lower classes in Ireland. This same woman, who had so wickedly calumniated my grandmother, afterwards made public confession of her guilt in the market-place at Kingston, on purpose to ease her guilty conscience, had done. I mention this, to show upon what slight grounds the planters exercise their cowskin whips, not sparing even an old woman of seventy years of age. But to return—

After the death of Lady Douglas, who was brought to England to be buried, James Charles Sholto Douglas, Esq. my mother’s, master, promised her her freedom on his return to Jamaica, but his covetous heart would not let him perform his promise He told my mother to look out for another master to purchase her; and that her price was to be £100. The villain Cruikshank, whom I have mentioned before, offered Douglas £10 more for her; and Douglas was so mean as to require £110 from my mother; otherwise he would have sold her to Cruikshank against her will, for purposes the reader can guess. One Doctor Campbell purchased her; and in consequence of my mother having been a companion of, and borne children to my father, Mrs. Campbell used to upbraid her for not being humble enough to her, who was but a doctor’s wife. This ill-treatment had such an effect on my mother, that she resolved to starve herself to death; and, though a cook, abstained from victuals for six days. When her intention was discovered, Doctor Campbell became quite alarmed for his £110 and gave my mother leave to look for another owner; which she did and became the property of a Doctor Boswell. The following letter, descriptive of her treatment in this place appeared in “Bell’s Life in London,” a Sunday paper, on the 29th February, 1824:—

Robert's Letter to Bell's Life in London

“TO THE EDITOR OF ‘BELL’S LIFE IN LONDON.’

February 20th, 1824.

Sir,—Your observations on the Meeting of the Receivers of Stolen Men call for my sincere thanks, I being a descendant of a Slave by a base Slave-Holder, the late James Wedderburn, Esq. of Inveresk, who sold my mother when she was with child of me, HER THIRD SON BY HIM!!! She was forced to submit to him, being his Slave, though he knew she disliked him! She knew that he was mean, and, when gratified, would not give her her freedom, which is the custom for those, as a reward, who have preserved their persons, with Gentlemen (if I may call a Slave-Dealer a Gentleman). I have SEEN MY POOR MOTHER STRETCHED ON THE GROUND, TIED HANDS AND FEET, and FLOGGED in the most indecent manner, though PREGNANT AT THE SAME TIME!!! her fault being the not acquainting her mistress that her master had given her leave to go to see her mother in town! So great was the anger of this Christian Slave-Dealer, that he went fifteen miles to punish her while on the visit! Her master was then one Boswell his chief companion was Captain Parr, who chained a female Slave to a stake, and starved her to death! Had it not been for a British Officer in the Army, who had her dug up and proved it, this fact would not have been known. The murderer was sentenced to transport himself for one year. He came to England, and returned in the time—This was his punishment. My uncle and aunt were sent to America, and sold by their father’s brother, who said that he sent them to be educated. He had a little shame, for the law in Jamaica allowed him to sell them, or even had they been his children—so much for humanity and Christian goodness. As for these men, who wished that the King would proclaim that there was no intention, of emancipation,—Oh, what barbarism!—

* * * * *

Robert Wedderburn

No. 27, Crown Street, Soho.”

I little expected, when I sent this letter, that my dear brother, A. Colville, Esq. of No. 35, Leadenhall Street, would have dared to reply to it. But he did; and what all my letters and applications to him, and my visit to my father, could not accomplish, was done by the above plain letter. The following is the letter of Andrew, as it appeared in the same paper on the 21st of March last, with the Editor’s comments:—

A. Colvile replies to Robert Wedderburn

BROTHER or NO BROTHER—“THAT IS THE QUESTION?”

A LETTER FROM ANOTHER SON OF THE LATE SLAVE-DEALER, JAMES WEDDERBURN, ESQ.

Our readers will recollect, that on the 29th ult. we published a letter signed Robert Wedderburn, in which the writer expressed his feelings in bitter terms of reproach against the atrocities of the man he called his Father, practised, as he declared them to have been, upon his unhappy Mother, and who was, as he stated, at once the victim of his Father’s lust and subsequent barbarity. When we inserted the Letter alluded to, we merely treated on the horrors of the station generally, to which Slavery reduced our fellow-beings, but without pledging ourselves to the facts of the question, as narrated by the son, against so inhuman a parent. But we are now more than ever inclined to believe them literally true; since we have received the following letter by the hands of another son— apparently, however, a greater favourite with his father than Robert—and in which the brutalities stated by the latter to have been practised upon his mother, are not attempted to be denied. The following letter we publish verbatim et literatim as we received it—a remark or two upon its contents presently:—

“TO THE EDITOR OF ‘BELL’S LIFE IN LONDON.’

Sir,—Your Paper of the 29th ult. containing a Letter signed Robert Wedderburn, was put into my hands only yesterday, otherwise I should have felt it to be my duty to take earlier notice of it.

In answer to this most slanderous publication, I have to state, that the person calling himself Robert Wedderburn is NOT a son of the late Mr. James Wedderburn, of Inveresk, who never had any child by, or any connection of that kind with the mother of this man. The pretence of his using the name of Wedderburn at all, arises out of the following circumstances:—The late Mr. James Wedderburn, of Inveresk, had, when he resided in the parish of Westmoreland, in the Island of Jamaica, a negro woman-slave, whom he employed as a cook; this woman had so violent a temper that she was continually quarrelling with the other servants, and occasioning a disturbance in the house. He happened to make some observation upon her troublesome temper, when a gentleman in company said, he would be very glad to purchase her if she was a good cook. The sale accordingly took place, and the woman was removed to the residence of the gentleman, in the parish of Hanover. Several years afterwards, this woman was delivered of a mulatto child, and as she could not tell who was the father, her master, in a foolish joke, named the child Wedderburn. About twenty-two or twenty-three years ago, this man applied to me for money upon the strength of his name, claiming to be a son of Mr. James Wedderburn, of Inveresk, which occasioned me to write to my father, when he gave me the above explanation respecting this person; adding. that a few years after he had returned to this country, and married, this same person importuned him with the same story that he now tells; and as he persisted in annoying him after the above explanation was given to him, that he found it necessary to have him brought before the Sheriff of the county of Edinburgh. But whether the man was punished, or only discharged upon promising not to repeat the annoyance, I do not now recollect.

Your conduct, Sir, is most unjustifiable in thus lending yourself to be the vehicle of such foul slander upon the character of the respected dead—when the story is so improbable in itself—when upon the slightest enquiry you would have discovered that it referred to a period of between sixty and seventy years ago, and therefore is not applicable to any argument upon the present condition of the West India Colonies—and when, upon a little further enquiry, you might easily have obtained the above contradiction and explanation.

I have only to add, that in the event of your not inserting this letter in your Paper of Sunday next, or of your repeating or insinuating any further slander upon the character of my father, the late Mr, James Wedderburn, of Inveresk, I have instructed my Solicitor to take immediate measures for obtaining legal redress against you.

I am, Sir, your humble Servant,

A. Colville.

35, Leadenhall Street, March 17th, 1824.”

As to our Correspondent’s threat of prosecuting us, &. we have not time just at present to say any thing further on this subject, than to remind him that he is not in Jamaica, and that we are not alarmed at trifles; so trust he will summon to his aid all the temperance he is master of, whilst we proceed to the task he has imperatively forced upon us. Out Correspondent, A Colville, says, that he is the son of the late James Wedderburn, and that our other Correspondent, Robert Wedderburn was so called in jest; and that his own mother did not know who was the father of her own child.—All this may be good Slave-Dealers’ logic for aught we know—but how stands the case at issue? Two parties say that each is the son of James Wedderburn; and, without knowing either of them, the assertion of the one is equally good as the assertion of the other, as far as bare assertion will go. But Robert states that he was the “third son” of James Wedderburn by the same mother; and here we must seriously ask Mr. Colvile, if such statement be correct, whether he means to tell us that the whole family was made by accident, or that the mother herself could not, owing to “her violence of temper,” on oath, positively swear whether she had any children or not? As to the “foolish joke” of calling a child after its father, we are ready to admit that many a Slave-Dealer would feel himself offended at such a liberty taken with his name; and the more especially where he intended to turn him into ready money by disposing of him—a practice with Slave-Dealers, of which our present Correspondent, we presume, is not entirely ignorant. However, if he be in reality, as he says, one of Wedderburn’s children, it is evident that the ceremony of calling a child by the name of its father has been dispensed within his own case, of which the difference between the name of his father and himself are striking proofs. But it seems, that Robert Wedderburn is not entirely unknown to A. Colvile, nor was he to James Wedderburn, “having applied for money” to them both, “on the strength of his name”—This matter, as it aimed at the pocket, A. Colvile perfectly remembers, “but whether the man was punished”—a consideration of much less importance certainly—he “does not now recollect.”

But we must now call the attention of A. Colvile—“the real Simon Pure,”—and more particularly of our readers, to the next paragraph of his letter, in which we are informed that we have been guilty of “lending ourselves” to “foul slander upon the character of the respected dead,” because—what?—why, because “the story is so improbable in itself,” and refers “to a period of between sixty and seventy years ago, and therefore not applicable to any argument upon the West India Colonies!” Although this is excellent reasoning—inasmuch as it has stood the test of time, having been urged between sixty or seventy years past,— yet it is of that obvious description that spares us the necessity of replying to it. But wherein we appear most culpable in the eyes of this affirmed son of James Wedderburn is that we did not, by “inquiry,” obtain the “contradiction,” which we have now so fortunately obtained?— But we are really too busily employed to hunt out the Solicitors of Slave-Dealers’ children, for the purpose of inquiring who are so fortunate as to be acknowledged as such, and who are so unfortunate as to be disowned by them.— Yet, after all, the intelligence we have obtained by the above letter, is but a “contradiction” of an assertion, without one single proof that the assertion is untrue.

We now flatter ourselves that A. Colvile will entertain a more favourable opinion of our love of equity than he appears to have done hitherto? We have inserted his letter, as it was his wish we should do, although we assure him it has not been from fear of any “dread instructions” which he may have confided to his Solicitor.

One word more, by way of advice, and we have done:—Concerning Robert Wedderburn and A. Colvile, each tells us that he is the son of James Wedderburn. Slave-Buyers, we are aware, frequently have many children born to them by this dreadful species of female property—when dearest ties of consanguinity are trampled upon by a sordid thirst of interest, we had almost said inherent, in the Slaver. Yet, let not this unnatural feeling extend to the offspring of such connections—an offspring that should be the more closely cemented by the ties of affection. as mutual sorrows are attendant on their births;—let, then, the bonds of sympathy lighten the bondage to which they were (however unjustly) born; and if Providence favours the one, let him strive to meliorate the distresses of the other. A father’s marriage makes him not the less the father of his own children, in the eye of Heaven, though borne to him by his Slaves; and we should feel much greater pleasure to hear if A. Colvile were to relieve R. Wedderburn (who, by the way, has not mentioned his name), than in his attempt to prove that a mother does not know the father of her child, and that child, as we are informed, the third she had borne to him!

Robert Wedderburn Replies

The next Sunday, 28th March, I replied to brother Andrew’s statement; and I will leave the reader to judge which had the best of the argument.

BROTHER or NO BROTHER—“THAT IS THE QUESTION?”

We this day publish a third letter upon this, certainly not uninteresting, subject—from him who declares himself to be the elder branch of the general stock; and if this be true, we must—en passant—in the first place, address a word or two to the younger scion—a Mr. Colvile—(we here insert the name as he himself has spelt it) will perceive by publishing the annexed letter, that we do not “lend ourselves to foul slander, &.” as in a moment of ridiculous petulance he was, last week, pleased to aver—but we shall hope that our publication of the little vituperative anathemas denounced against us in the epistle with which he honoured us, has, ere this, convinced him how grossly he libelled us in the assertion. However, we forgive his irritability, and will venture, once more, to give him a little advice as to his future literary communications. If, as he has asserted, the writer of the following letter be not his brother, instead of using idle threats of setting his Solicitor upon us, let him seat himself soberly down in his closet, and send us the result of his temperate reflections upon the subject in question. Let him remember also, that his argument will lose nothing by good language, nor be the less convincing by being urged in terms not unbecoming a gentleman. It may not, perhaps, be improper, once more remind Mr. Colvile that the publication which first offended him made no allusion to himself—and he must make great allowances for the warmth of feeling expressed by a man whose natural sympathies have been so deeply wounded as those (according to his own statement—and of which he adduces corroborative facts) of Robert Wedderburn. Let Mr. Colvile send us a statement of facts that will disprove the statements of Robert Wedderburn, and Mr. C. shall soon be convinced that—to speak in his own phrase—“we do not lend ourselves to be the vehicle of foul slander,” but are really, what we pretend ourselves to be, and what every public journalist ought to be—the Advocates of Truth and Justice. Mr. C. cannot think that we ever had the least intention of injuring or offending him, aware as he is that we did not know that there was such a being as himself in existence until he told us so; and as we are of no party, our columns are as open to one part of his father’s family as to another.

But Mr, Colvile asserts in his letter of the 17th instant, that the case therein referred to, as published by us, “was not applicable to any argument upon the present condition of the West India Colonies.”—As to a matter of opinion, we must beg leave to differ with him: length of time is no argument against the inhumanities of Slave-Dealers, as practised against the unprotected Slave. Many years ago it was acknowledged that the power of the West-India Slave Dealer had been by him abused, but that the condition of his live stock was now [then] meliorated. The self-same argument is urged with equal vehemence at the present day; and such would be the never-failing salvo for ages to come, were the wretched captives to be left to the mercy—we beg pardon—to the cruelty of their fiend-like masters: and here we must remind Mr. Golvile that this is not merely our own opinion upon the subject, but was the language of British Senators when commencing the benevolent work of casting off the chains of their fellow men. We would wish to act with becoming delicacy to Mr. C. or to Mr. Any-body-else, under similar circumstances, unless forced to cast it aside by him or them—but we say (for we have made certain inquiries since we published his letter) that we should have expected that he would have been one of the last to have spoken with indifference on the sale of his fellow creatures. Let us merely suppose that his own mother had been treated as many of the unhappy mothers of Slave-Dealers’ children have been treated, what, then, we would ask, must have been the feelings of any man not lost to all sense of humanity?—And is it not a matter of chance, where interest preponderates to induce him to marry—who of a Slave-Dealer’s children is born to him in wedlock, and who is not? Mr. C. has not yet informed us whether or not he was born in wedlock, nor do we either know or care.—We will repeat to Mr. Colvile what we have often before repeated, viz. our unalterable conviction that the man who accumulates wealth the blood of his fellows, must ever be dead to the feelings common to our nature. But although we have said we would never cease to exclaim against the horrible traffic in human flesh until there was an amelioration of the condition of Slavery; yet, unjust as is the argument of force against the force of argument, we wished not an instantaneous emancipation, although we could have wished our Ministers to have gone farther than they have done, and extended their object to the other Colonies, as they have already commenced it in Trinidad. However, as it is, we rejoice to find that there is a beginning to soften the rigour of captivity and fetters; but, as Mr. Wilberforce truly observed, the consequence of disappointed hope might be to drive the Negroes to “take the cause into their own hands.” With him take that such may not be the case!

We now return to the point from which we have so far, and not unnecessarily, we think, digressed. The columns of our journal are ever open to redress any wrong we may have unintentionally committed; but we are not to be threatened into silence upon a subject, the truth of which, in some material points, is not even attempted to be denied, or disproved by corroborative circumstances; and if Mr. Colvile will not follow the good advice we have already bestowed upon him, he would do well to address himself to that Ultra-Radical or Loyalist,—who so jumbles his extremes, we know not which to call him—the Infamous John Bull.—In his columns Mr. C. may hack, cut, and quarter the Slaves ad libitum. It is true, indeed, that thus, many thousands of our readers may not see the ink-engulphed massacre, but perhaps the general carnage may make amends for this deficiency? However. Mr Colvile will please himself in his future operations; and, just hinting to him (should he address the Infamous John Bull) the propriety of passing by the Scotch Cow, alluded to in the following letter, we recommend it to his perusal without further ceremony:—

“TO THE EDITOR OF ‘BELL’S LIFE IN LONDON.’

Sir,—I did not expect, when I communicated my statement, as it appeared in your Paper of the 29th ult. that any person would have had the temerity, not to say audacity, to have contradicted my assertion, and thereby occasion me to prove the deep depravity of the man to whom I owe my existence. I deem it now an imperative duty to reply to the infamous letter of A. Colvile, alias Wedderburn, and to defend the memory of my unfortunate mother, a woman virtuous in principle, but a Slave, and a sacrifice to the unprincipled lust of my father.—Your Correspondent, my dear and affectionate brother, will, doubtless, laugh, when he hears of the virtues of Slaves, unless such as will enhance their price—but I shall leave it to your readers to decide on the laugh of a Slave-Dealer after the picture of lust and cruelty and avarice, which I mean to lay before them. My dear brother’s statement is false, when he says that I was not born till several years after my mother was sold by my father:—but let me tell him, that my mother was pregnant at the time of sale, and that I was born within four months after it took place. One of the conditions of the sale was, that her offspring your humble servant, was to be free, from its birth, and I thank my God, through a long life of hardship and adversity, I have been free both in mind and body: and have always raised my voice in behalf of my enslaved countrymen! My mother had, previously to my birth, borne two other sons to James Wedderburn, Esq. of Inveresk, Slave-Dealer, one of whom, a mill-wright, works now upon the family estate in Jamaica, and has done his whole life-time; and so far was my father from doubting me to be his son, that he recorded my freedom, and that of my brother James, the millwright, himself, in the Government Secretary’s Office; where it may be seen to this day. My dear brother states that my mother was of a violent temper, which was the reason of my father selling her;—yes, and I glory in her rebellious disposition, and which I have inherited from her. My honoured father’s house was, in fact, nothing more than a Seraglio of Black Slaves, miserable objects of an abandoned lust, guided by avarice; and it was from this den of iniquity that she (my mother) was determined to escape. A Lady Douglas, of the parish of St. Mary, was my mother’s purchaser, and also stood my godmother. Perhaps, my dear brother knows nothing of one Esther Trotter, a free tawny, who bore my father two children, a boy and a girl, and which children my inhuman father transported to Scotland, to gratify his malice, because their mother refused to be any longer the object of his lust, and because she claimed support for herself and offspring? Those children my dear and loving brother knows under the name of Graham, being brought up in the same house with them at Inveresk. It is true that I did apply to my dear brother, A. Colvile—as he signs himself, but his real name is Wedderburn—for some pecuniary assistance; but it was upon the ground of right, according to Deuteronomy, xxi. 10, 17

‘If a man have two wives, one beloved and another hated, have borne him children, both the beloved and the hated, and if the first-born son be her’s that was hated;

Then it shall be, when he maketh his sons to inherit that which he hath, that he may not make the son of the beloved first-born before the son the hated, which is, indeed, the first-born;

But he shall acknowledge the son of the hated for the first-born, by giving him a double portion of all that he hath, for he is the beginning of his strength, the right of the first-born is his.’

I was at that time, Mr. Editor, in extreme distress; the quartern loaf was then 1s. 10½d., I was out of work, and my wife was lying in, which I think was some excuse for applying to an affectionate brother, who refused to relieve me. He says that he knew nothing of me before that time; but he will remember seeing me at his father’s house five years before—the precise time I forget, but A. Colvile will recollect it, when I state, that it was the very day on which one of our dear father’s cows died in calving, and when a butcher was sent for from Musselburgh, to kill the dead beast, and take it to market—a perfect specimen of Scotch economy. It was seven years after my arrival in England that I visited my father, who had the inhumanity to threaten to send me to gaol if I troubled him. I never saw my worthy father in Britain but this time, and then he did abuse my mother , as my dear brother, A. Colvile, has done; nor did he deny me to be his son, but called me lazy fellow, and said he would do nothing for me. From his cook I had one draught of small beer, and his footman gave me a cracked sixpence—and these are all the obligations I am under to my worthy father and my dear brother, A. Colville. It is false where my brother says I was taken before the Sheriff of the County—I applied to the Council of the City of Edinburgh for assistance, and they gave me 16d. and a travelling pass; and for my passage up London I was indebted to the Captain of a Berwick smack.

In conclusion, Mr. Editor, I have to say, that if my dear brother means to show fight before the Nobs at Westminster, I shall soon give him an opportunity, as I mean to publish my whole history in a cheap pamphlet, and to give the public a specimen of the inhumanity, cruelty, avarice, and diabolical lust of the West-India Slave-Holders; and in the Courts of Justice I will defend and prove my assertions.

I am. Sir, your obedient Servant,

Robert Wedderburn.

23, Russell Court, Drury Lane”

In Conclusion

I could expatiate at great length on the inhumanity and cruelty of the West-India planters, were I not fearful that I should become wearisome on so notorious a subject. My brother, Andrew Colvile, is a tolerable specimen of them, as may be seen by his letter, his cruelty venting itself in slandering my mother’s memory, and his bullying in threatening the Editor with a prosecution. I have now fairly given him the challenge; let him meet it if he dare. My readers can form some idea Andrew is in a free country, and what he would be in Jamaica, on his sugar estates, amongst his own slaves. Verily, he is “a chip of the old block.” To make one exception to this family, I must state, that Andrew Colvile’s elder brother, who is now dead, when he came over to Jamaica, acknowledged his father’s tawny children, and, amongst them, my brothers as his brothers. He once invited them all to dinner, and behaved very free and familiar to them. I was in England at that time. Let my dear brother Andrew deny this, if he can, also.

I should have gone back to Jamaica, had I not been fearful of the planters; for such is their hatred of any one having black blood in his veins, and who dares to think and act as a free man. that they would most certainly have trumped up some charge against me, and hung me. With them I should have had no mercy. In a future part of my history give some particulars of the treatment of the blacks in the West Indies, and the prospect of a general rebellion and massacre there, from my own experience. In the mean time, I bid my readers farewell.

R. WEDDERBURN.

23, Russell Court. Drury Lane.

Printed and published by R. Wedderburn, 23, Russell Court, Drury Lane.